Here is the ride of April 24-25, 1926.

During the last run, Tom and I had tried to get the Seveners to support a proposed all-nighter, said ride to be somewhere about Betws-y-coed, but a strange apathy seized them, and vague references to certain unavoidable appointments were made. Notwithstanding this, we were determined on the ride, which we said would be a ‘strainer’ for Meriden, three weeks hence. Our meeting place was Mrs Littler’s, Frodsham at 7pm for supper. The intervening 26 miles were covered in the leisured style demanded for such occasions, the two of us reaching Frodsham at the appointed time. Joe was there, too, not to join us, but gaze upon the alleged beauty of one Maid Marion, to whom he hopes to press his suit. Joe’s flirtations are many and always terminate suspiciously abruptly.

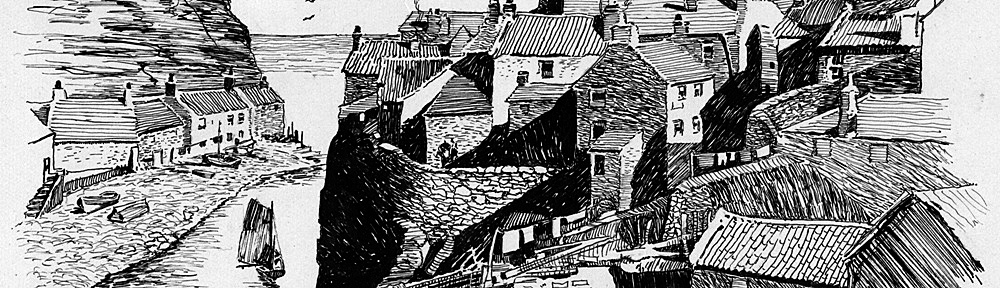

It had gone 8pm when Tom and I left Joe making eyes and sped along the darkening Chester road. Efforts to obtain bitter chocolate, an excellent stimulus, failed everywhere, so that we had to make a dash to the City of Legions before closing time. We managed it. Then, not really knowing where we were going, we crossed the Dee bridge and turned our wheels towards Holywell. Saltney and its dismal flats were put behind, and in growing moonlight we passed through quiet Hawarden and by moonlit meadows and parklands steadily forged our way to Northop, and at length fled down to Holywell. After that we struck a barren stretch, up and down with a long line of telegraph poles always in front, but even the worst has an end, and that was reached when a glaring disc announced that we were about to descend a ‘Shell Famous Hill’. We stopped for a snack before descending, for a cold-looking mist overhung the lowlands. A cyclist went blinding past, fled out of night, then we heard a curious crack, and a minute later he came back to us with a broken chain. He had no brake; how on earth he managed to stop I don’t know, but by his bombastic talk we soon formed opinions of him – as a cyclist at any rate. As he only lived a few hundred yards away we didn’t need to help him.

From the foot of the ‘Shell’ hill we had a short run through agricultural country to the tiny city of St Asaph. With hardly a pause we were out and in the country again. At half past midnight, half light and warm, and I was wide awake, a surprise to me for I anticipated a bad night – I had been working all morning. Soon the country became level, again, almost monotonous, and we reached the site of a great camp. Eight years ago the countryside here was teeming with khaki-clad figures; there on the left was a town, a wooden town that housed them. I had the privilege of visiting this huge camp ten years ago, though, as I was only 12 years of age, the only things I can remember clearly are rows and rows, endless rows of identical wooden huts, wooden post offices, wooden libraries, wooden canteens, even wooden roadways, a continual mud bath (I had to clean my shoes in those days) and the constantly recurring khaki of the inhabitants. Before the end of the long rough fields and tottering remains of the timber houses was reached, the slender spire of Bodelwyddan marble church emerged from the half-light of the evening, and as we drew nearer to it, the great contrast it provided to the depopulated ramshackles there on the left that 8 years ago housed men, struck me forcibly.

In the neat little churchyard, looking out towards the remnants of the camp are rows of little wooden crosses, the burial places of Dominion soldiers who fell victim to the influenza epidemic which, in 1917 swept through the camp like a plague and carried off so many men. How many more, trained at the camp, went out, and now lie on foreign soil ? The war to end war, the hope of those who fought – and died……. what would they think now ? Now on the very eve of the greatest struggle in industrial history, when their comrades are about to fight again – for the right to live in decency. Despite all the pious resolutions, despite all the promises, despite all the hopes, we are heading for another great catastrophe. And the verse:

“If ye break faith with us who died,

We shall not sleep, tho’ poppies grow

In Flanders fields…..”

is proving to be nothing more than one more hollow sham. What would the dead army of Britain say to their comrades who fought and lived – to fight to live ? “Fight on !” Such thoughts are bound to come to the man who thinks, when he passes such a symbol of ugly war as Kinmel Camp, and comes upon the pure white symbol of peace, as represented by the Marble Church of Bodelwyddan, at a time when the rest of the world sleeps.

A perfect road, though level and dismal enough carried us over the marshlands of Morfa Rhuddlan to Abergele, where we had decided to try the road to Llanrwst, which neither of us knew. Tom went in front while I adjusted my lamp, and before I followed I was treated to a series of double-bass snores, extremely loud and trumpety, issuing from one of the upper windows in the quiet street. I’ll never forget Abergele at 1.15am if only for that ! After a level run in park-like country, the road got on its hind legs, and we had to shank it for a mile or so, into an upland plain, which we crossed on a switchback road and found ourselves running down into a valley flanked by hills not very high, but continuous enough to give us the idea that the only outlet would be ‘over the top’. We felt the old glamour returning of cycling on unknown roads in unknown country, the glamour that so marks the first tour and is never quite regained. We wondered what lay round the next bend – over the hill, where this lane or that lane led to; in our pockets was the complete answer embodied in a map, but just then we wanted no map; we would find out for ourselves and keep ourselves on the tip-toe of expectation. Down the side of a wooded hill we sped, in and out, round and round, through a veritable pass until we found ourselves beside the stony Elwy, where a stone-built village lies across a stone bridge. I hear that Llanfair Talhaiarn is an interesting little place, but 2am in the morning is no time to scrounge in and out of a narrow-streeted village, is it ? The road was good and level, winding below the hillside, so, having been imbibed all night with a very energetic feeling, we ‘slipped it’, coming at length to Llangernyw, which village was kind enough to supply us with water on tap and stone steps to recline on whilst we ate our ration.

To judge by the row we made one way and another its perhaps all to the good that we went when we did. Then, as we were peacefully blinding along, the very devil loomed up from a field on the right, a big black body with waving arms and clawlike hands stretched out in silhouette as if to grab us. Our hearts leapt in terror. A second timorous glance revealed a dead tree – our flickering eyes supplied the rest ! A gradual climb now came which got us down more than once, but surely enough the country on each side was opening out, until we reached the summit from whence we got a peculiarly fine view of ranges of misty peaks across the deep gap into which we started to descend, and which resolved itself into the Conway Valley.

As we pounced downhill the misty peaks dropped behind the lower heights on the western side of the valley which, in the dim light, made a glorious picture. Rather recklessly we plunged into Llanrwst, promptly getting mixed up and playing ring-o’-roses round what does for the village hall. After a glance at Inigo Jones’ bridge, we blinded along the Llanrwst side of the river to Betws-y-coed where, at the Waterloo Bridge, a powerful electric light robed the woods, the river Conway, and a pretty little cascade in golden glamour. Childs play was made of the drag up to the Swallow Falls, where, by the hotel, we discovered another tap over a tub of clear water, whilst behind the wall was a bath should we want it. We didn’t ! Here also was a natural lamp-bracket, just in the right place, a towel rock (natural) and a natural mirror (water). We had soap and a towel with us and the proverbial half-comb with most of the railings missing, so, in plain lingo, we were ‘quids in’. We had a jolly good tub, then, fit to enter a palace, we shinned over the turnstile and went down to take the customary peep at Swallow Falls.

Riding again, we soon came in sight of Moel Siabod, in my eyes like an old friend greeting us once more. Some call this a dull mountain on the Capel Curig side, but I love Moel Siabod, and would hail it as I would our old friends Snowdon, Trifan, Arenig and Cader Idris. As a matter of fact all these grey old mountains of the Wonderland of Wales are old friends to me. Very soon, we stood at the familiar fork-roads at Capel Curig; the time was 4.30am.

Should we make for Beddgelert or Bangor, was the problem, but we favoured Beddgelert, as providing the better homeward route. So we passed the twin Llyn Mymbyr which gave a perfect reflection of the mountain sides, and headed up the wild Gwryd Valley, with the first streaks of dawn crossing the eastern sky and the dusky outline of Snowdon away in front. Pen-y-Gwryd was an impressive spot when we got there at 5am. Above us towered the graceful form of Eryre, partly snow-clad, above a semi-circle of great, silent cliffs; above the long, broken screes; above the chaos of earth and rock that supports it. A tousled, sleepy head peered down at us from a hotel window, and Tom, just to let him know we had seen him, shouted a cheery good morning, to which came a sleepy answer and the head withdrew. Simultaneously I started to munch an iron ration in the shape of a crust as we started towards Beddgelert. Iron ration is the right phrase for it, for I had a great tussle with that crust.

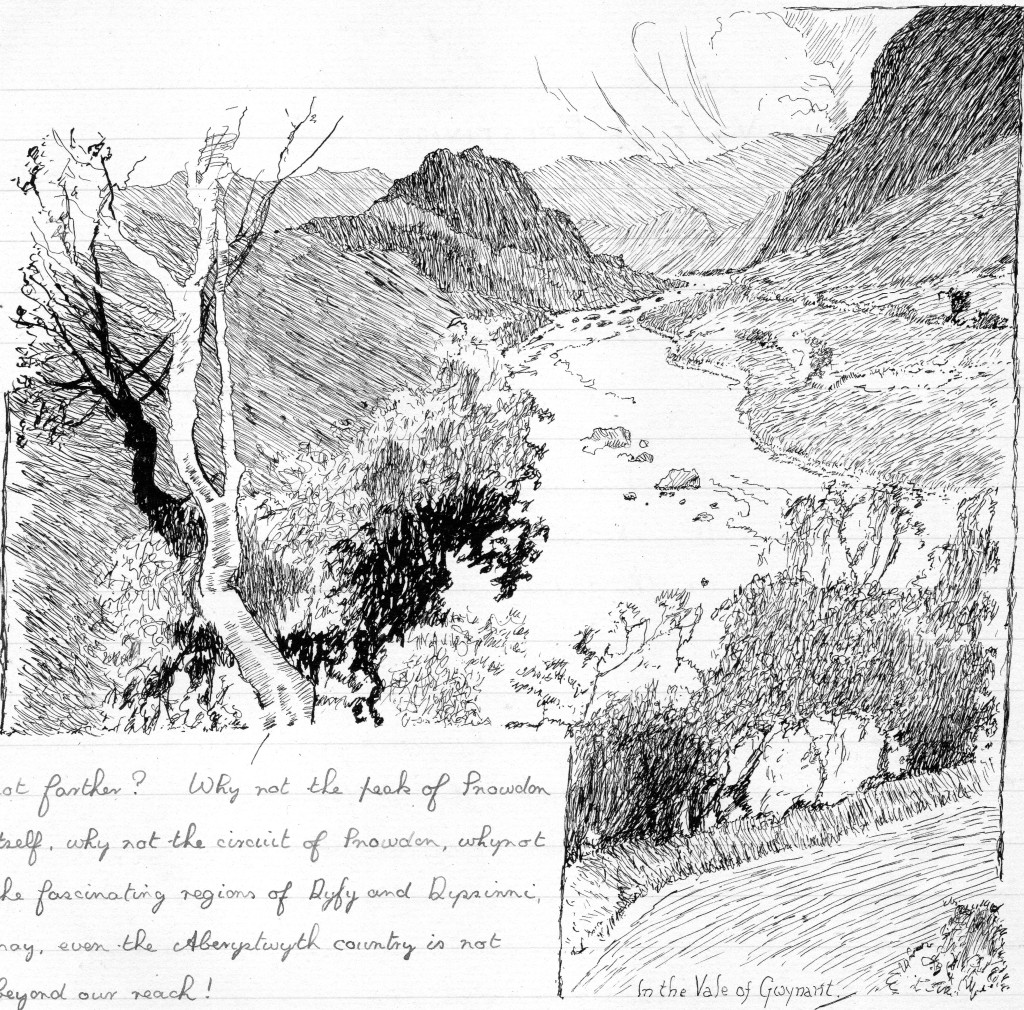

They say a crust is a good thing to eat whilst cycling, and I heard of chaps who put up long rides on a crust, but all I can say is that they don’t know what a good feed is ! A taste of real Wales again fell to us on that long descent to Beddgelert. The soft light of early morning between dawn and sunrise put a wonderful freshness into the greenery of Gwynant and toned the great cliffs and boulder slopes of Snowdon down to something above mere grandeur. Ever and anon we would stop that we might take in the views more fully, pay fuller homage to the Queen Peak and this loveliest of Welsh valleys. Llyn Gwynant formed a most perfect mirror, reproducing topsy-turvy, in minute detail, every overhanging rock, every branch and leaf, every blade of grass – in colour. The scenery was a continually moving panorama of mountain views and woodland and water scenes, holding us spellbound at every turn, making us gasp in sheer delight at being there at such an hour. Everything was familiar to us, for we oft had passed along this Valley of Waters, but everything was new…. old but new. Llyn-y-Dinas was another great mirror, lapping the roadway, and doubling the lakesides perfectly.

We entered glorious little Beddgelert, stopping there on the bridge for a moment before pushing on into the Pass of Aberglaslyn – and Pont Aberglaslyn. Aberglaslyn at 6am, just before the sun tinged the mountain tops with his golden light, just when the life of the woods was stirring and singing the joys of the new day accompanied by the musical chatter of the river. That was Aberglaslyn at its best. I fancy the first effects of our hard-riding was becoming felt just then, for Tom swore he saw a man hewing trees down by the dozen with amazing energy – and when I was shown, I saw the same thing. Of course, it was a fantasy aided by vapour rising from the ground. I saw the trees shaking and the cliffs bobbing up and down, and wondered at it all in a dull uncomprehending way until Tom, in a distant voice, said that we had best get along. Then as I started to ride, my sleepiness dropped off like a cloak. Riding along the edge of the Glaslyn marsh, we beheld many natural glories, and from the War Memorial at Garreg the most magnificent view of Snowdonia I have ever seen was laid before us. The great peaks, from sea level, looked higher than ever, and the great ridges culminating in the central peak were touched with silvery bars of snow, whilst on the right of us stood the splendid peaks of Cricht, and rugged Moelwyn Mawr, just below which the route we had decided to take, lay.

Once again the superb attraction of Ffestiniog proved too strong for us. On that steep, narrow pass from Garreg to Tan-y-Bwlch, I started to feel the ride again, and ere the tiny hamlet of Rhyd was reached I yearned for a mattress and a pillows. Superb mountain views rewarded us, and from Rhyd, where a gap occurs in the hills on the right, we saw the coastline from Penrhyndeudraeth southward with the profile of Harlech and its sheer rock standing out. Again luck was with us, for we found a little waterfall and a bucket. Another wash, and another temporary relief from sleepiness. Passing through stony, tiny Bwlch-y-Maen, (which means Pass of the Stone), we got a beautiful view down into the Vale of Ffestiniog, then descended to Llyn Mair. If anyone asked which was the most gorgeously pretty lake, irrespective of size in Wales, I think I should answer Llyn Mair. I cannot recall a more charming picture than that which Llyn Mair presented that morning with its amazingly clear reflections. The descent through woods to Tan-y-Bwlch was as in a fairy-land; Spring was at her best, and in the Vale of Maentwrog the freshness of everything green struck me – that is, everything except myself. On the climb to Ffestiniog I went to pieces, and fairly shouted with relief when Tom punctured. I dragged myself into Ffestiniog to order breakfast, but had to knock Mrs Jones up; Tom arrived just as I sank into the armchair. It was 8am and a rapid calculation showed that since 5pm last night we had placed 130 miles of road behind us.

I made a poor show at breakfast, and even when Jennie, pretty and sly as ever, came down, I paid little heed – so I must have been in a bad way ! In a sleepy way I became aware that my leg was being pulled, but I was past caring about it; I’ll get my own back next time. After I had managed to drag my bones into the parlour, Jennie gave us a selection or two on the organ, and what with one thing and another it got 11am before we made a move to go. There was well over a hundred miles to go, and a strong headwind to face, so we had something before us. We started after the usual lingering farewell at the usual brave pace uphill and got off round the corner – as usual. The long climb, half walking, knocked the sleepiness away from me, and I began to sit up and take notice. It was a beautiful morning, clear and breezy, and the dear old line of peaks stood clear and sharp above the winding Vale of Meantwrog which stretched out green below us to the coast. Rhaiadr Cwms steady road greeted us as we neared Pont-ar-afon-Garn, and to renew acquaintances we peered over the stone wall at the cliffs and the ‘Cataract in the Hollow’.

From Pont-ar-afon-Garn the going was easier, but we struck the ‘newly repaired’ portion, and for four miles spent a lively time alternating between sharp stones and deep ruts. Especially after we had topped the breezy summit and seen the bulky form of Arenig grow larger in front and the Ffestiniog mountains drop behind the summit ridge, we experienced the vilest stretch of road in Wales – and that is saying a lot. From Rhyd-y-Fen we left the worst behind finding it positively smooth going over the rocky outcrop in comparison. From Capel Celyn we romped down to Fron Goch and Bala from where the Corwen road bore us on its glossy hide uphill to Bethel. I ‘conked’ again on that grind uphill, and the eleven miles to Corwen were more like a hundred and eleven. Near here, on the Holyhead road, Tom went on to Llangollen to order lunch while I had a rest and a snack, improving afterwards. The Dee valley is very beautiful, but when the road is one long string of motorists, it loses much of its attraction, so I hailed Llangollen, and, incidentally ‘Bronant’ with delight at 3pm. During lunch and the usual ‘chatting up’ after, I was nodding, and would surely have gone to sleep if I had been left to my own devices. As it was it got to 4.30pm before we got away.

It was very hard against the wind, but by pacing each other we got along fairly well; moreover I felt myself gradually improving. The setts of Wrexham are enough, however, to rouse anybody. We parted at Chester, Tom taking the Northwich road and I the Warrington road. Now I was in better form, having gained the proverbial second wind and did good time to Frodsham where I stopped for tea at 7.45pm. I could not help but reflect on the things that had passed since we were here 24 hours ago and the huge circle we had undertaken. At 8.30 I was back on the road, in my old form, still against the wind, and on familiar roads reached home at 10.30pm.

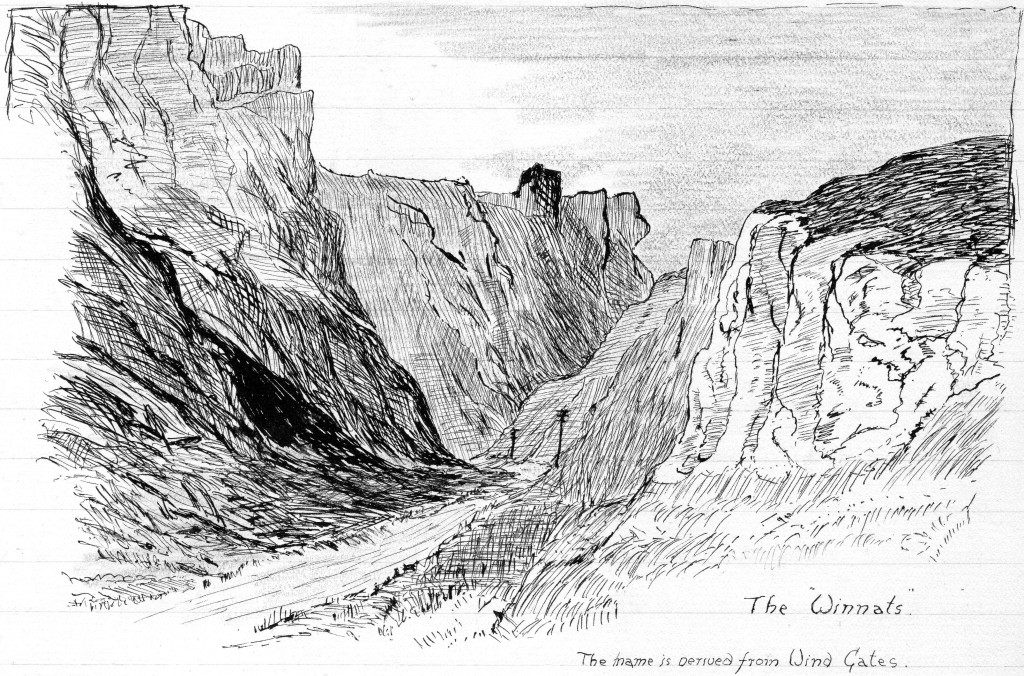

In September 1922, I had a three day tour of 230 miles, and the following Easter, a four day tour of 290 miles. On this all-night ride of 29 hours (which includes at least seven hours in cafes at Ffestiniog, Llangollen and Frodsham), we covered about 245 miles, 155 of which were in Wales. But more than mere mileage was the inference one can draw from this ride. No doubt I was in a bad condition, owing to the lack of sleep, but that could be minimised by better preparation or a morning free. It has opened the door to greater things. We have proved the possibility of reaching Snowdonia and returning in a night and a day, we have visited Beddgelert and Ffestiniog, hitherto undreamed of – so why not farther ? Why not the peak of Snowdon itself, why not the circuit of Snowdon, why not the fascinating regions of Dyfy and Dyssinni, nay, even the Aberystwyth country is not beyond our reach !

So has gone down three of our Welsh nocturnals; the rest I will describe in some further article, for a continuous description of the similar kind of ride is apt to get monotonous, especially from a pen like mine ! December 1926