Part 3 At the Edge of the Cairngorms

We were camped just outside Ecclefechan, in August 1931. Under Mrs McCall’s hospitable roof we had lingered out the last remnant of daylight. A cyclist from near Lanark had beguiled us long with deeply interesting talk of his own romantic Lowlands. In darkness we had found a campsite in a field at the edge of the village.

During breakfast we consulted our pockets and pooled our resources. I had come away from Mrs McCall’s with just a shilling; now Jo turned out twenty-seven shillings and fourpence, which did not seem such unbounded wealth, especially if the prospective remittance at Fort William did not materialise. Jo had also brought a pound each of butter and bacon and a few dainties – the only ones we appeared likely to get. To add to our embarrassment, we were charged two shillings for the site. We departed far more angry at the over-charge than we were concerned at our poverty. Lightly enough we faced the strong wind which promised us a difficult passage all day.

Trouble was lagging at our heels, and eleven miles from Beattock caught us up. With a great sigh my rear tyre sank to the rim. A great hole the size of my fist spelled ruination to it. At a road-side counsel we gleaned the information that a garage lay two miles ahead, so off I went on Jo’s bicycle with the exchequer sitting already too lightly in my hip pocket. I was out of luck; the sterile Scots Sabbath was on the place. Returning to Jo, who sat patiently waiting beside the ruin, we debated afresh. There was a sporting chance at Beattock, if only we could limp the distance. Jo discovered a large piece of canvas in her kit, and this we stitched on the old cover, mended the puncture and slowly proceeded. The bulge was painfully apparent ere we had gone far. At length we reached a tiny cycle shop with the very tyre we required in the window, but the people refused to serve us. It was the Sabbath; the Sabbath must not be broken. No matter how desperate the straits, how urgent the need, your true Scot will not disturb his delicate sense of religion, nor endanger his soul by thought or deed. At Beattock a garage-man had less compunction. Ten minutes later we were jovially pushing forward up the windy glen of the Elvan Water, a new tyre below me, and in pocket only eighteen shillings and ninepence separating us from a tinker’s existence.

A slow dour fight over the water-shed and through Abingdon led us into Clydesdale, and as evening approached, Lanark, my campsite of last night, was regained. Soon after Lanark, Jo fell lame with knee trouble, a legacy of two day’s struggle against long odds. A valiant attempt to keep up the pace petered out, stabbing knives seemed to tear at one knee, and it soon became clear that she could travel little farther and that little, slowly. To add to this we ran into a black part of Lanark industrialism, coal, iron and brickworks. It was irritating country inasmuch as we were often led into believing we had made open country by a growing spaciousness of fields and estates, when the climbing of a ridge would reveal a skyline of pits and chimneys. The people themselves were no more than half savage, shouting suggestive remarks and laughing offensively at Jo’s shorts. A girl may walk through the Wigan coal-field clad in the scantiest summer clothes, but there is no embarrassment caused, but here the men hailed us, the women screamed abuse, and the children set up catcalls. The limit was reached when they began to throw sticks and stones. Meanwhile Jo’s knee became almost unbearable. At a point near Newmains, where a single colliery stands amid green fields, we found a farm where the people were very kindly, allowing us a pitch where-ever we wished, and afterwards engaging us in converse for a long time.

Monday morning was nothing to enthuse about. We awoke to rain, a raging wind dead east, and as cold as any February day. The rain stopped later, but black galleons of cloud raced in succession across the bare width of sky, promising nothing but the likelihood of bad weather. There was not the shadow of a mountain nor the green livery of a wood to relieve the low horizon – drenched ricks of hay, a thin, wind-beaten hedge – that was all. Jo’s knee was stiff and an early recurrence of the pain was feared. The scenery alternated between colliery and green fields, and once, on the edge of a big town – Airdrie – we crossed the harsh highway between Glasgow and Edinburgh. Riding carefully, walking the long hills that began to appear, the stiffness gradually wore out of Jo’s knee, and in ten miles she was riding in fair comfort. The threat of rain passed off, and with it the brutality out of the wind, leaving a naggy headwind with a glorious broken sky. Our hearts were lifted at a view of the broad Vale of Forth with Stirling crowded below, and behind the graceful Ochil hills. Far away to the west the Highlands stood, those fine Trossachs peaks, Ben Ledi, Ben Vorlich, Ben Venue, barely scraped by the layered clouds – a thrilling gateway to the wild Beyond.

We reached St. Ninians and had to go to Bannockburn, to the stone where the Bruce raised the standard of a united Scotland, there sending the English Henry flying back. There is a high flagstaff with a standard unchallenged, a little hut at one side where picture postcards are sold, and a man tells the tale of that gruesome affair – for a consideration. We saw him eye us over, and so, five hundred and seventeen years later, came a second English flight!

I like old, historic places like Stirling, because they make me dream on the uneasy past, and I become thankful that I live in modern times when the chances of torture and sudden death lie only along the highway. In Jo and I there are no illusions about the ‘good old days’. Heroics are fine – on paper, read in a snug armchair; we are all for the present when one’s opinions are only silently suppressed, one’s politics, blood red though they be, are ignored, and religion need not interfere with one’s love of wholesome worldly pleasures. The most a man may lose with his tongue is his job, and that needn’t cause bitter tears to flow. Stirling was the distributing centre for raiding parties as well as the bone of contention ‘twixt Highland and Lowland. The gibbets never lacked their gruesome, swinging loads; the sanitary arrangements were left to themselves in the streets; the common folk were under the heel of a feudal system that enslaved them mind and body to the whim of the Laird. Stirling was building itself up in blood and misery for the days when curious tourists could pry around and pay credulous coin to hear history moulded to suit their delicate senses.

Jo went shopping. The peculiar feminine delight of alternating from shop to shop, pausing in uncertain contemplation of half a dozen variations of one desirable delicacy is beyond my accounting. I should have rushed into the first shop and concluded the business in a couple of minutes. I am told that all this philandering about is for motives of economy, but when I recalled the purchase of four twopenny postcards for tenpence halfpenny I was told I did not understand. I don’t.

Bridge of Allan was dull. With a mind full of Banks of Allan Water and Miller’s Lovely Daughter, with whom I had sorrowed for many a long year, my dream was found to be shattered. Most fond illusions break thus.

This is the land of battlefields. There was Bannockburn, and Stirling Brig, where Wallace defeated the English in 1297, and a little way along the Perth road we passed close by Sheriffmuir where the Earl of Mar met Argyle in the rising of 1715. There was a battle, a sort of comic opera engagement, in which both sides got badly scarred. Some wit has improved the occasion with rhyme:

‘Some say that we wan,

Some say that they wan,

Some say that non wan at a’ man,

But one thing is sure,

At Sheriffmuir

A battle there was that was fought man’

At Gleneagles, nearer to Perth, international battles of golf are fought nowadays. The going was hard to Perth, a nagging wind and rolling road, with ever glimpses of the blue Highlands westwards. At the summit of a final ridge we overlooked the winding kinks of the River Tay, Perth below, and the tidal sands eastward towards Dundee.

We saw little of the clean, nicely built town. A small shop supplied our stores; a supper bar lined us for a further few miles, which was the Blairgowrie road, first by the broad Tay on whose surface floated gaily a high proportion of Perth’s younger populace. The sun was setting; behind the mountains the colours were sprayed from deep red through infinite shadings to gold, and into the pale blue of a clear sky. The mountains were in indigo contour. The wind had fallen.

Jo’s knee began to crook again, and so, eight miles out of Perth a turfy hollow by a stream screened from the chilly night winds of these northern latitudes attracted our attention. There we pitched. There was a wholesome smell above the primus stoves at supper time. Stewed plums and custard; coffee and rolls. Conversation.

The Lairig Ghru was now a practical impossibility, for even now we should have been camping in the jaws of the pass, at least forty-five miles further on, with the highest road in Britain between. Obviously something else would have to be planned, shorter, less arduous. In any case Jo’s knee would not stand the tremendous strain of hours of struggling across the debris and scree of that high remote pass, which splits the heart of the great Cairngorms. We turned in, deciding to let the morrow take care of itself.

We had decided to re-model our mode and, by getting away early, camp earlier in the evening, enjoying a more leisured sunset hour. At 6am we startled the sleepy cattle by the stream, and loud in brief ablutions, hurried towards breakfast.

Very shortly we came to Bridge of Isla where the road runs beneath a great hedge of beech trees, a hundred feet high, a third of a mile long, and planted in 1745, a memorable planting in such a time of uprooting. Approaching Blairgowrie we were struck by the number of encampments, tinker, bastard gypsy, and individual tents and caravans. Raspberries are cultivated extensively here, and we saw many at work among the rows of succulent berries. At a stream men stood bare-legged, scrubbing barrels out. The neat little town of Blairgowrie gave us entrance to the glen of Ardle Water. The sun shone, a gentle zephyr replaced the high wind, and all the promise was of a golden day. Jo’s quick eyes spotted wild raspberries growing along the hedges much as our English blackberries do. For an hour we worked along a hundred yards of hedge, in our enthusiasm crossing a derelict fence, to berries that never grew wild. With only five shillings left, we packed our panniers with the nucleus of a good meal. Pink jelly oozed through the bags, our hands were stained for days, and when, a little higher up the glen Jo complained of tummy ache, I learned why we had collected so many berries for one meal.

The scenery became grander as the road climbed higher, with a wooded ravine below and glimpses of rapid waters. At Bridge of Cally in six miles the Ardle stream bent westwards with the Pitlochry road, and we entered Glen Shee, a barren depression along which the river chattered on its stony course. By the hamlet of Persie we had riverside lunch, nineteen miles behind us, thanks to our three pounds of raspberries steadily dripping themselves away. With the typical uncertainty of the Highland climate there came a gust of wind, grey mists blew over the peaks and crept down the glen, gradually obliterating the landscape. A touring cyclist, dawdling along, joined us in a hurried dive into capes, and with us struggled along the tilted road. The rain passed, but the mist held fast, hiding the high peaks about us. Our new companion, a Londoner with three weeks ahead of him, a last fling ere he got married, he confided, caused heartaches to my partner who was silent for some time in rapt visualisation of what we could do with such a holiday. With unseen mountains edging closer, we passed the Spittal of Glenshee at 1,118ft, climbed higher and harder into a cold northerly wind, mile upon mile until, in a final upward convulsion round the Devils Elbow we reached the summit of Cairnwell pass. This is the highest main road in Britain, 2,200ft. For twenty miles we had been climbing, for twenty miles the scene had been changing from the green beauty of the glens to the grey mists swirling over brown and black wilds.

On Cairnwell summit the northerly wind screamed in our faces and on it came sleet, cold as a winter gale. The vaporous abyss of Glen Clunie yawned below, yet in spite of the fierce down-grade we pedalled hard to hold our own. For a few brief moments the mists broke, and far ahead, through the ragged frame, we caught a glimpse of great mountains and the white streak of a snow-filled Cairngorm corrie. The vision of moments, the treasured memory of years!

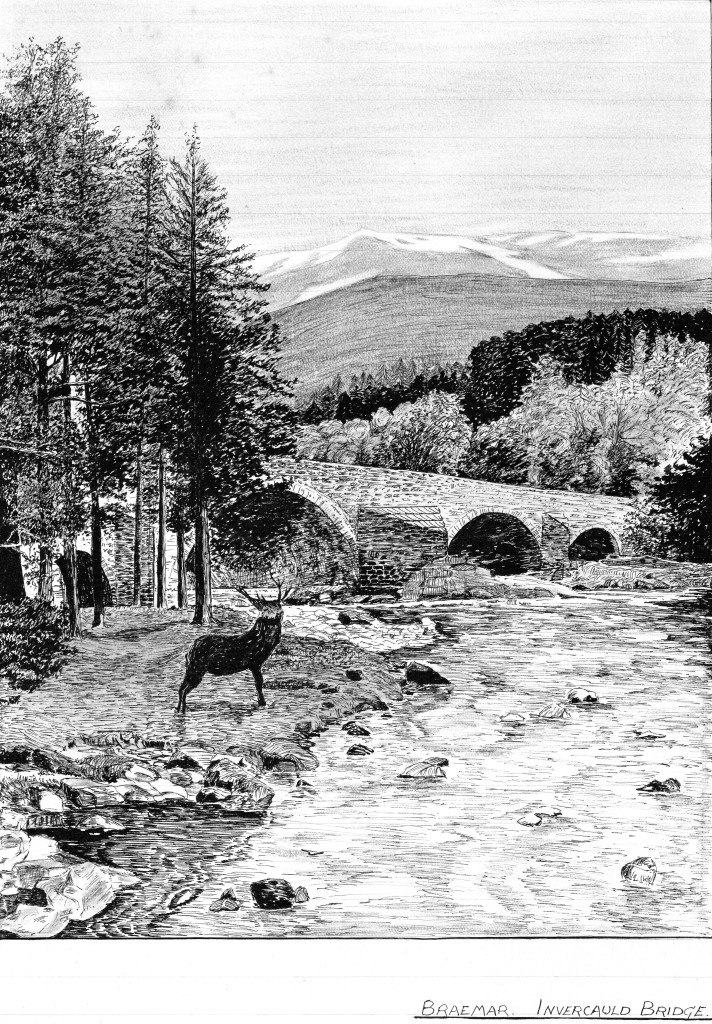

The teeth chattered with genuine cold all the way down the wide desolation of Glen Clunie. There is an old Wade bridge by the new road, spanning a river in spate; lower down Clunie Castle stood in a thin belt of trees like a tall man half naked. The rain ceased, the wind died away, the road became dry, and we entered Braemar in the Dee valley, ‘Royal Deeside’ some say.

Braemar is the kind of place that breeds snobbery; amongst very expensive things in very select shops are a few very cheap things like the magnificent viewcards at a penny each. After the purchase of our humble necessities we dashed our ship of economy upon that stall, until only a wreck was left to us. There was a magnificent limousine outside a hotel. Presently there emerged from the place a vast bundle of furs which moved with infinite poise infinitely slowly to the waiting car. A very servile chauffeur arranged a luxurious pile of cushions and humbly placed my lady amidst them.

Braemar is the kind of place that breeds snobbery; amongst very expensive things in very select shops are a few very cheap things like the magnificent viewcards at a penny each. After the purchase of our humble necessities we dashed our ship of economy upon that stall, until only a wreck was left to us. There was a magnificent limousine outside a hotel. Presently there emerged from the place a vast bundle of furs which moved with infinite poise infinitely slowly to the waiting car. A very servile chauffeur arranged a luxurious pile of cushions and humbly placed my lady amidst them.

This opulent parasite must have become aware of our contemptuous grin for we were given a haughty stare calculated to freeze us. The stare went wrong; we had to laugh at her. Jo suggested we kidnap her and force her to cross the Cairngorms afoot with us, sharing for food the remains of the raspberries which still shed their lifeblood steadily. She would have reached the Great Glen a better woman for it.

The Lairig Ghru was out of the question of course, and except for turning back, only one practical course remained if we would make for Fort William – a long trek through the moors of Geldie Burn and Glen Feshie to Kingussie. We calculated the distance to be about thirty-three miles of which only twelve or so are rideable, leaving a central distance of twenty-one miles to walk, scramble, get over as best we could. Too much of a conjecture for our London friend who said goodbye and fled down the Dee valley in search of the luxuries of life. We had our kit, the time was 5pm, and we had laid in stores for the night – iron rations for two nights if need be. There were two shillings left. A hundred miles away, at Fort William, was the possibility of a remittance. Failing that, well, we would have nearly four hundred miles to go…… And both of us were quite unconcerned.

To the Linn of Dee our road ran through thin belts of pine amongst which the timid deer flitted nervously; across the river the mists brushed the pine-tops of Glen Quoich. In spate, the Linn of Dee was almost terrifying, boiling under the bridge and flinging its white foam into a sheer sided chasm. Thereafter the bridle road emerged into the wide moorland basin where the Tilt and the Geldie Burn join the peaty Dee. White bridge crosses the Dee in a setting of austere wildness, magnetic to the mountain lover. At this point the narrow defile of Glen Dee comes down from the heart of Cairngorm – the Lairig Ghru itself stretched into the twilight mists. Jo was affected; I was saddened. A thought cherished for years, three attempts, and twice so near – she found it very hard to leave – for how many years?

In the gathering darkness the road was not worth riding. We passed a ruined clachan, grimly set above the chattering Geldie. The track was interminable, running level in a monotonous wilderness. Grey tongues of mist curled; nights shadows hung overhead, hesitating to fall; and the light mountain rain fell steadily. We sought a camping place but bog, rock, and gullies where peaty water spouted was all we could find.

Desperately weary, we reached a footbridge over the stony burn, and there, at 1,650ft we found enough hummocky grass to pitch our tents. At midnight there was still grey light, but in half an hour, when we turned in, black night had closed and even the noisy stream half a yard away was invisible