Part Three: Around Snowden

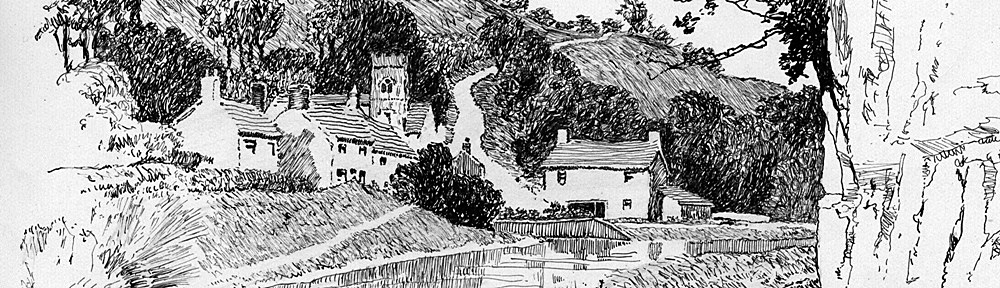

The verse came upon me as I looked through the bedroom window, at Beddgelert and the mist-wreathed heights above, the heights whereon Ailwyn had wandered in search of his lost love, where he had heard her playing the harp so sweetly under the crags of the Knocker’s Llyn. I would advise anyone to read Ailwyn if they love a good, classic novel which is woven round, and set upon, the stage of reality. I was first down, and had the pleasure of meeting one Mary, who for beauty compares with Jennie of Ffestiniog. When I went up and told Billy and Joe about her, they were up like a shot ! It was here that we heard a true animal story that is worth recounting from the lady of the house (‘Florence Nightingale’). It started through an enquiry of mine about a poem framed on the bedroom wall, in Welsh, and in which the words ‘Beddgelert’ and ‘Eryri’ aroused my curiosity.

Many years ago, when she was a child, she had a brother who tended sheep on the slopes of Snowdon. He possessed two dogs named Cymru and Prince, who were always with him. It was his custom to call at the farm for his meals and come home to Beddgelert at night. One day, when snow lay thick on the mountains, he did not appear for dinner at the farm, and at teatime he was absent too, but only when he did not come home at night did his people become anxious, and a search party was sent out. After a night of vain searching the party returned, and were just about to turn out again, when Cymru, the dog, came bounding in and started to paw at them and run towards the door. They let the dog have the lead, and he took them over the foothill onto the screes on Snowdon, where they found the boy below a crag, with Prince, the other dog standing sentinel over him. He had slipped over the cliff in the snow, and was killed, and while one dog had gone to find aid, the other had stayed to guard his body. The boy was buried in the little churchyard at Beddgelert, and often the two dogs could be seen sat solemnly over his grave.

Outside a thick low mist hung over the mountains almost hiding them altogether, and our hopes of climbing Snowdon began to fade. I was quite willing, if only for the sake of the climb, but Joe and Tom saw nothing in it, as only the views made it worth while in their mind. So we rearranged our plans, settling on the Carnarvon road as one that none of us had hitherto traversed.

We ate over two loaves, generous loaves too, at breakfast, no remarkable thing when you consider that there were five of us, and five healthy cyclists can eat quite a lot between them. Owing to the position of the County border, we had supper in Shire Carnarvon, slept in Merioneth, and breakfasted in Carnarvon again. Dozens of people were about in the village, cyclists starting out, and two motorloads of merry cragsmen armed with ropes and rucksacks were just leaving as we turned out. The mists did not trouble them !

We found the first three miles a heavy drag through open country that would be rather dismal had it not been for the almost weird effects of the mists, which came to the road almost and seemed quite plastic, breaking and closing in solid palls, revealing sheer mountainsides and towering peaks, only to shut them in again almost immediately. Very probably in clear weather this road will give some wonderful mountain views. At Pitts Head (named after a rock that is said to show a good profile of the former statesman), the road started to descend and we speedily came to Rhyd-Ddu, where is the Snowdon Ranger Inn, an uncomfortable looking place at the foot of Snowdon. George Borrow mentions, in his ‘Wild Wales’, a chat with the innkeeper, who was a guide for Snowdon, and who called himself and his house ‘Snowdon Ranger’. In those days a guide was a necessity, for to the stranger Snowdon was a terrible and arduous climb fraught with dangers, for mountaineering had not found its way into the hearts of the people, and nobody seemed to care for the mountains. Rhyd-Ddu, a simple sounding name, is the usual stumbling block to the tripper. One calls it ‘Rid-do’, until a Welshman comes along and makes it unrecognisable by saying ‘Rhud-thee’ (Black Ford, it means). A little farther on is Llyn Cwellyn, which every guide book and map spell wrongly, calling it Llyn Quellyn. There is no ‘q’ in the Welsh alphabet. Llyn Cwellyn is a large sheet of water set deep in the mountains and over-shadowed by an awe-inspiring crag, Craig Cwm Bychan, tentacle of Mynydd Mawr. The road runs along the north shore and the crag stands to the southwest. The mists, hiding the upper portion, made it seem higher than it really is, and imported the same weird air of grandeur as at Beddgelert.

The others went on, leaving me sat on a wall admiring the scene, and it was full 20 minutes before I left. I came to Nant Mill, a pretty spot and an old flour mill with a water wheel, and then again it went dull, the mists, though not nearly so thick, hiding the hills, and houses lining the road. At Bettws Garmon an improvement was noticeable, and at the top of the next hill the mist disappeared and away below me stretched the fertile country around Llanwndda, fields and woods and villages and the sea, gleaming beneath the strengthening sunlight. From Waen Fawr I swooped down into Carnarvon, coming to rest by the castle. I found the others by the Straits. We did not go into the castle, though it was open (I had been inside previously), because the fine ruin looks best from the outside, with its massive gateway, walk, and imposing towers. After a short potter in the vicinity of the river Seiont, the Menai Straits and the castle, and accompanied by the stares of the townsfolk, we joined the Llanberis Road. The mists had, by now, entirely dispersed, and the sun bade fair to outshine all its previous glory, whilst, ever aware of the call of hunger, our speed became hectic except when a hill got in the way.

After some miles of rolling country that to me seemed wonderfully fresh and green, we stood on an elevation that brought us in view of the stunning array of mountains from each side of the Llanberis Pass. There was the Pass, an awesome looking defile over which hung the chaotic confusion of rocks which we call Snowdonia, as clear to behold as earlier it had been misty. The shining cliffs and boulder-strewn screes, the lofty peaks, all beneath a perfect sky, sent me madly longing to be amongst them, and to climb, climb, climb, until I finally reached the utmost height. Above all other scenery.

I love a high hill,

With its granite scars:

From Cwm-y-Glo we rode above the long, deep Llyn Padarn, across which the hillsides were ablaze in colour, and came to Llanberis. As everyone knows, Llanberis is a centre for Snowdon. The railway starts here for the summit, and also the most popular track. To the infirm or aged, the rack railway is a godsend, but why, oh why do so many physically fit people go by the railway? I hate it, it has lowered the prestige of the finest mountain in Wales, and though it has given many a chance of seeing the beauty of high mountains, it has encouraged others to ascend the peak by an inferior route. Then how many misguided folks climb to the summit on foot from Llanberis and regard it as a mountaineering feat when it is only a long and somewhat dreary walk? Their energy could be better employed on a more worthy route. I say to all who intend to ascend Eryri, to take the Capel Curig track, or Sir Watkins from Nant Gwynant, or the Snowdon Ranger route, and to those who are not afraid of a bit of real climbing, try the pathless screes to Cwm Glas and the easier pitches of Crib Goch It is only off the beaten track that one sees the real grandeur of the mountains, and where ‘Natures heart beats strong amid the hills’.

We stayed not in Llanberis, but at the end of the town, and just as we left the road to go up to the waterfall, we met the Bolton quartet, and the whole nine of us went along together. The river comes down in a leap of 30 ft or more into a rocky basin, being more of a very steep slide with a curious twist in the middle. A fair volume of water was coming down owing to last nights rains. It is named Ceunant Bach (Little Fall), which we did not see. Our return to the bikes was made in perfect formation, two deep, to the rendering, by a musically inclined member of Mark’s Troupe, of “Toy Drum Major”. As their direction was directly opposite to ours, we left them on the road, and once more headed for the Pass. In a little while we saw a ‘Teas’ notice in a garden and a lawn with easy chairs, so yielding to the temptation we ordered lunch and scattered ourselves all over the lawn in the hot sunshine. A party of Liverpudlians stopped, attracted by the notice, but we told them it was not much of a place, so they hied off. We could forsee a shortage of food if they joined us. As at Beddgelert they gave us the loaf to hack as we pleased, so we ordained Tom bread cutter, but after the first loaf he gave it up, as we were eating as fast as he was cutting, leaving him without. The second loaf was cut by Joe, but he too relinquished the task, and I took it over, cutting a loaf into five slices, giving each a slice. They charged me with cutting the thickest for myself, so as I had cut it wedge-shaped, I showed them the thin end, and they were satisfied. After four loaves we were still unappeased, and my turn came to go for more (we took the fearful job in turns). I got a shock when I was told there was nothing left, and when I informed the others they roared in laughter; Joe was doubled up in real pain, tears streamed down our cheeks, and we became helpless, but when a large cake came in we managed to shift it between our chuckles. Fancy five of us eating up the stock of a catering house !

Our next move was to the ancient round tower that is all that is left of Dolbadarn Castle, the last home of Welsh Independence. Situate on a little rocky knoll between Llyn Padarn and Peris, and commanding a view west down the lake to the country beyond and east up the Pass, it gives a true glimpse of Wales both wild and sublime. Glyder Fawr on the north side of the lakes has been quarried into vast steps, the whole mountain being entirely despoiled.

Once more we were riding, the precipice on each side drawing closer, until just beyond Nant Peris, we were in the Pass proper. Utter chaos reigns on each side of the road; from the high cliffs above, thousands of boulders have fallen, some breaking into tiny pieces, others perched on all kinds of seeming precarious positions, and others, great masses of rock have caused the road to be built round them. The heat was merciless, making it easier for us to walk rather than ride even when the gradient was easy. Near Pont-y-Cromlech a break appears in the line of cliffs on the right, behind which is the ridge of Crib Goch with the Snowdon summit peeping from behind. I had heard that up there is Cwm Glas, the wildest hollow in Wales, so I suggested a scramble up the screes to the hollow. So we abandoned the bikes and – well, elsewhere in this book will be found the story of that afternoon in Cwm Glas, and of the wonders unfurled to us. [The Narrow Way that leads to Paradise – Ed]

It was after 5pm when we were all united again, Billy and I climbed Llanberis Pass without stockings on, and the sight of our bare legs provoked every passer-by to merriment. We did not care: it would have mattered nothing if all the Principality had come to laugh at us. A treat awaited us at the summit. All the Capel Curig side was in a choking mist, whilst the Llanberis side was perfectly clear and sunny, then as we descended to Pen-y-Gwryd, the peaks appeared one by one above the mist, sharp and clear at first, then faint and distant looking, an effect that lent them the appearance of being immensely high. Again the mist covered everything, and then the sun, a faint ring, broke through above the ridge of Lliwedd. When we reached Pen-y-Gwrd, the valley was flooded with brilliant sunshine, whilst a few yards higher, the mist cloaked everything. Weird and wonderful is the only way to describe the continuous moving pictures caused by the mists on that switchback down to Capel Curig. There were the Snowdonian pinnacles jutting from a white sea, here on the left a precipice reared into a snowy blanket, on the right a line of billows cut Moel Siabod in two, yet in front everything was as bright and clear as it ever could be.

We had a great tea at a place we knew at Pont Cyfyng, one mile south of Capel, and arranged to stay the night, so Tom, Billy and I decided to have a sprint as far as Nant Ffrancon, Joe and Fred being too lethargic.

We turned our wheels back to Capel Curig, continuing along the Holyhead Road. Over Snowdonia the mists still clung almost, one might say, affectionately, and Siabod still retained its snowy girdle. Our way now lay into that great glacial hollow between the rough old Glyders and the expansive Carneddau. Twilight, a beautiful quiet twilight, broken only by the even hum of tyres on the glossy highway, or the steady hiss of the chains over the cogs, had settled on the mountains which lay before us in a frowning range of crags – not frowning, for the crags cannot frown at an hour like this. This smooth road is excellently graded, so the five mile climb was child’s play, though we blinded it all because we wanted to get amongst the crags ere dark. Two cyclists who were en route from Manchester to Bangor made interesting company, and, though riding roadsters, in long trousers etc, they had all the makings of “real” cyclists. When at last we gained the proximity of Llyn Ogwen, it was almost dark. We rode by the lake, which, at first, brightly streaked with rippling reflections, had now changed to deep gloom. Left of us, the ragged crags of Trifan rose for over 2000 ft to the three points which loomed unreally overhead. Ogwen Cottage, the climbers hostel came into view, we stopped, bade the Mancunians goodbye, and dumping the bikes, we joined the rickety track that leads to Cwm Idwal. Boggy, stony and darksome was the way, so the half mile or so took much longer than in daylight, but at length we found ourselves beside the Lake of Darkness, Llyn Idwal.

Ringed by boulder-strewn screes and over-shadowed by great cliffs, there is an awesome grandeur about this spot that is very fascinating; its fascination and that of the towering crags around has lured many to climb – and many to death. We sat down on the rocks by the waterside and watched the darkly rippling wavelets, the black, pinnacled mountains, and the sky, a deep velvet pricked with a million points of light. Oh, inspiration, impulse!; that urge to go forth and do something great, the thoughts that arise from the mind, when the urge of the mountains are upon one ! None of us spoke, yet we all spoke, in thought, but which we all understood and heard. It was the tone by which the note of genius is struck, and finding us barren of the quality, it implanted itself upon our minds as an engraver in metal stamps his subject. The Romance of it all, too ! The Romance of Idwal, and the tragedy that for ever darkened the waters of the Llyn, the romance of that terrible chasm in the cliffs ahead, where many men have climbed their last, and the romance of the Cymric battle for independence. The very cliffs and boulders breathe it !

It was a long time before we tore ourselves away, and, still in deep reverie, stumbled up a low mound from where we looked down the Nant Ffrancon Pass, where the last bright streak of day was merging into night over Anglesey. The great gap with its still silvery thread of a river, a vivid contrast to the blackness of the hollow, and the two pinpoints of light from a motorcar slowly ascending towards Ogwen, still live vividly in my mind. Our way back to Ogwen Cottage was something of an adventure over bog and boulders in Stygian gloom, and when we regained the road we walked to Ogwen Bridge to listen to the water as it escaped from the lake and leaped down the crags ere it wandered down the ‘Vale of Beavers’ to the sea. Then we remounted our bikes and slowly pottered back between hoary Trifan and the overshadowed depths of Llyn Ogwen, until the lake and the Pass and those wonderful old mountains were behind and the open moors in front, the darkness being broken here and there by the light of some farmhouse set below the mountains. Ugh! It grew suddenly cold, icily cold, then we entered a clammy mist. We had to feel our way slowly down to Capel Curig, the while a chilly breeze blew right through us. At Capel the mist miraculously disappeared, and a backward glance revealed the white curtain hanging over a strip of country – we had passed through it. Snowdonia was still as we had left it, and Siabod’s girdle had not moved at all; how tenacious it was !

Our first thought when we reached Bryn Afon (our place for the night) was to be against the fire; then supper. Once again we were to sleep abroad, fully three minutes walk away, in a house of which opinions were soon formed, but a minute search of the bed and effects hardly failed to confirm our beliefs, and the night passed comfortably enough.