Jo’s enthusiasm runs high on the unexplored. When she is prospecting the possibilities of forgotten passes and ancient pathways she could not be happier, unless it be upon the actual exploration. Every dotted line across the hill-shading of our maps is sure to receive attention sooner or later. The fascination of the ‘dotted line’ dates from the first time she cast eyes on an Ordnance Survey in her earliest cycling days. Someone had informed her that all dotted lines are tracks, and Jo implicitly believing, set her heart upon a certain wavering, heavily emphasised line that passed from peak to peak in the rough regions of Shap, regardless of the laws of natural contour. The route lacked any track, but Jo’s boundless enthusiasm carried her over a long series of disheartening obstacles before she discovered that she had been attempting to trace a county boundary !

Jo’s enthusiasm runs high on the unexplored. When she is prospecting the possibilities of forgotten passes and ancient pathways she could not be happier, unless it be upon the actual exploration. Every dotted line across the hill-shading of our maps is sure to receive attention sooner or later. The fascination of the ‘dotted line’ dates from the first time she cast eyes on an Ordnance Survey in her earliest cycling days. Someone had informed her that all dotted lines are tracks, and Jo implicitly believing, set her heart upon a certain wavering, heavily emphasised line that passed from peak to peak in the rough regions of Shap, regardless of the laws of natural contour. The route lacked any track, but Jo’s boundless enthusiasm carried her over a long series of disheartening obstacles before she discovered that she had been attempting to trace a county boundary !

In the course of time one learns to understand maps more thoroughly. Experience is a hard teacher, and in the case of exploring alleged tracks encumbered with a bicycle the lessons are sure to be remembered. Difficulties crop up which people who never leave the roads cannot imagine. It is generally believed that Britain is a settled country where Nature is well tamed, but that is far from the truth. A man may yet get lost and never be seen again, or may wander for days in desolate land without habitation of any sort. Paths over the mountains are often too faint to be traced with certainty; climatic conditions may be such as to make a moderately difficult passage impossible, even in summer. The person who frequents the solitudes faces, at times, pitiless conditions which call for determination and much careful thought. That is half the pleasure of it. He alone has the right to say if it is worthwhile.

High Cup Nick is a natural phenomena in the limestone of Cross Fell, and is reached by a track of sorts [now part of the Pennine Way] between Teesdale and the Vale of Eden. The name, High Cup Nick, is very expressive. It fascinates. Jo had talked of it for months, a prelude to certain action at the first opportunity, for High Cup Nick is just beyond the range of an ordinary weekend. The chance came when the Cotton strike of 1932 took place. Jo works in the mill, I was unemployed. As it was desirable to cover much ground by Saturday evening, we arranged that Jo should leave Preston soon after noon, and I should follow with all speed from Bolton. By thus minimising delay we hoped to make camp on the high ground between Brough and Middleton-in-Teesdale, a hundred miles from home.

After a long dry spell, the weather had broken. A night or two of heavy rain and drenching showers during the day with strong westerly winds told too plainly of the best we could hope for. I started late, riding hard across the paths of many a fierce downpour until the turn for Quernmore valley put the wind dead behind. After tea I entered Lunesdale. The river was a swirl of spate; at Caton by Lancaster it flowed brown and full-lipped, encroaching the low fields; at Kirkby Lonsdale 12 miles higher the river boiled over the rocks in mad endeavour. All the twentysix miles of the Dale to Sedbergh were changing panoramas of threatening clouds in a windy sky, brown fells reflecting the sky in moods from sullen to gay, and always chattering waters within sound. Dusk in Rawtheydale, a gradually rising road, the noisy stream at hand, shapely mountains between which the road pursued a winding way. Cautley Spout was a white flake in a ravine already filled with night. Jo was still ahead; I lit my lamp and rode harder along the lonely highway, over its final steeper pitches to the black, windy summit from which the dim lights of Kirkby Stephen lay scattered below. At 9.30pm in that highland railway town the silence of sleep had already settled. Under an inky canopy I crossed the Vale of Eden to Brough, that ancient, stone-built village clustered below the ruins of its castle. Brough lives in less fearful days now – Brough was abed and secure, with only the wind wandering abroad.

Jo was riding well. I had seen nothing of her, and felt the cold hand of doubt. Was she really ahead? I could only go on. The wild road that crawls over the fells to Middleton-in-Teesdale pulled me up, and I faced a long walk uphill. High above me a light flashed, and hopefully I signalled back. The light remained stationary, so I hurried until I came within hail. “Thank Heaven it is you!”, came the response, “I’m tired out”.

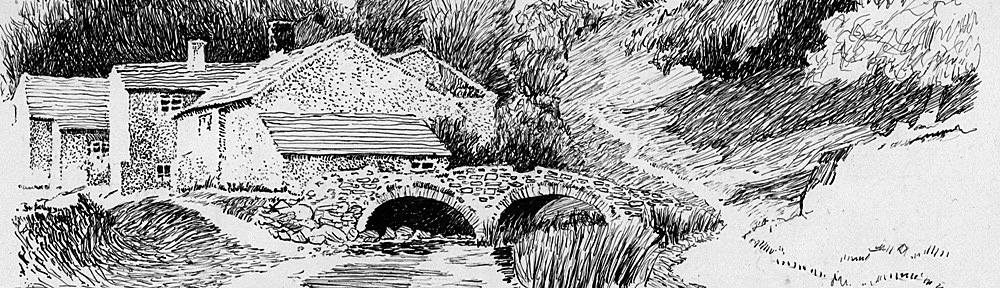

Jo had waited until after the usual time, then fearing I had got away early, she had hurried. For eighty miles we had chased each other with no more than a few minutes between us! Below the summit there was a bridge over a peaty burn; gratefully we camped in the lee of it.

The morrow began cold and stormy. A passing shepherd peeped in to congratulate us on the choice of a comfortable place on the rain-sodden fells and held our attention with tales of winter storms and inky mists when even these weathered old hill-men had lost themselves for hours at once.

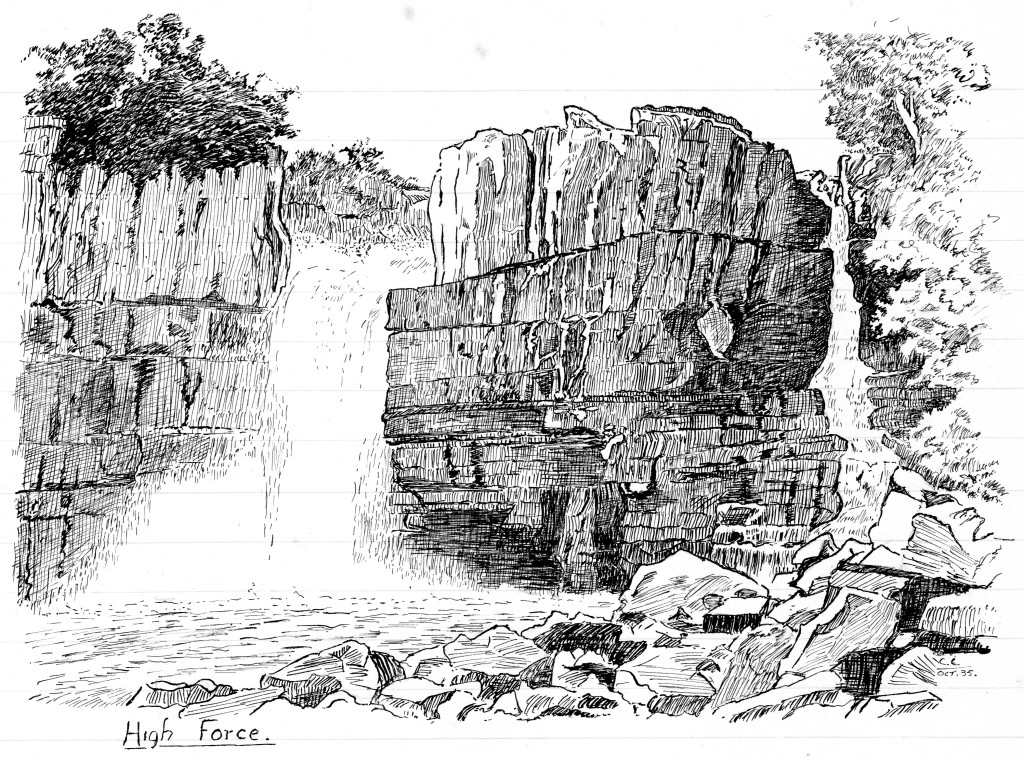

Our journey eastwards crossed a high ridge at 1,574 feet and took us over miles of purple moorlands swept in turn by sun and rain, till Teesdale lay below, and we swooped down into Middleton. The main road up the dale gave us a hard struggle in the teeth of the wind. We saw the distant fleck and heard the roar of High Force a quarter of a mile away heading the steep ravine. The next half hour yielded three miles of hard pedalling to Langdon Beck, where we abandoned the highway. This road, on its way to Alston, becomes the highest main road in England at 1,942 feet. This is a land of high roads threading their difficult ways over the highest Pennine – the bleakest country below the Cheviot.

Behind a wall we shivered through lunch, a meal which terminated abruptly in a rush of rain. We tramped along a stony track for four desolate miles of successive summits, wind and rain raking us all the time, and ahead on Cross Fell, such a grey swirl of cloud as might dishearten less enthusiastic travellers. The track, in a shocking condition, tumbled us down to Cauldron Snout, that waterfall with the expressive name which must surely bring many people enquiring ‘what’s in a name?’ Normally the Tees descends a series of great steps; this day it was a raging slide of white water, fearful to look upon, and shaking the very earth about it. At the foot of Cauldron Snout, Maize Beck pours in, forming the angles of three counties, Durham, Cumberland and the North Riding of Yorkshire. A decrepit hut close by saved us from a terrific storm that swept down from Cross Fell with an awful show of cloud. By a small bridge above the falls we gained access to Cumberland, and following the course of Maize Beck, through several fields – hardly won intake from the predominant moors – crossed stiles and gates to Birkdale, reputed the loneliest farm in England. We had tea there.

No modern complications disturb life at Birkdale. The nearest neighbour lives two miles away, the nearest village is eight, and the nearest railway station eleven and a half. From the first of May until the end of September the postman comes twice a week (if necessary), but for the remaining seven months not at all, the reason for which is plain to see when one looks round at the vast wilderness of black fells and their intersecting maze of peat hags with brown becks, so often unfordable. The old farmer spoke of long weeks of isolation when the snow makes the whole region inaccessible, the search for buried sheep, the relief when all are safely penned and the stock warmly stabled. All life marks time, waiting patiently for the release of Spring. Four people and a tiny baby, then only ten weeks old, shut away from the outer world, provisioned already against the Autumn floods. The young woman with the baby turned to Jo and said with deep fervour, “Oh, if I could only go to the warm south for a few weeks!” Even then, so early in September, the great shoulders of the Pennine had the stamp of winter upon them. She feared the winter with her baby in mind, but the old farmer thought more of the big thaws that change the clean, far-stretching snow into wild torrents of water.

Our host displayed interest when we announced our intention to cross the fells to Dufton in Edendale, eight miles away. Came questions. Were we used to fell country? Did we know of the hundred traps set by nature and the weather-demon? They were manifold on Cross Fell. Unwary travellers are better away, initiating themselves on the more gentle hills of the south, not causing trouble and inconvenience to the shepherd folks at the busiest season. His tone softened at our reply. We were no plains-people out on a day trip. Not strangers to the hills. Our whole beings were wrapped up in them. They were our life, and our experience was nothing light or shadowy.

The discouragement was not unjust. People often come to Birkdale for the purpose of crossing High Cup Head, usually day-trippers woefully unprepared in the matter of clothing and equipment, expecting to find a kind of mild moorland footpath. As a rule they come back hours later, baffled. One party set off at noon in high summer, wandered through the day and night, and regained Birkdale by a mere chance at 4am, utterly worn out. There was recalled the rare pluck of a girl who had twisted off the heels of both shoes, had limped through the night with a large nail drilling her foot, whilst both feet were badly cut and bleeding. She had suffered agonies, but had the spirit to smile and cheer the rest of the party. Commonly people came back to Birkdale later than midnight, begging for accommodation. The shepherd vigorously denied the existence of any track for the first two and a half miles, though the Ordnance Survey show one. He said he was willing to post the whole route if approached on the matter by the authorities, an offer that must be regarded as very generous. If there is mist about he advised nobody to cross.

[To be continued on Christmas Eve]